Imagine you have spent nearly 30 years in prison just for writing poems—the only thing that keeps you going is the hope of someday being reunited with your wife and family. But then when the day of your release finally comes, you discover that your family has been told that you are dead and you are left to wander the earth like a ghost, caught between the horror of the past and a present where you don’t even really exist.

Imagine you have spent nearly 30 years in prison just for writing poems—the only thing that keeps you going is the hope of someday being reunited with your wife and family. But then when the day of your release finally comes, you discover that your family has been told that you are dead and you are left to wander the earth like a ghost, caught between the horror of the past and a present where you don’t even really exist.

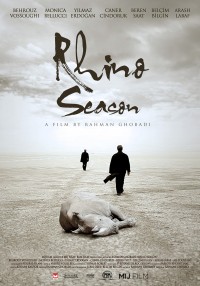

This is the tragic situation faced by the protagonist of a powerful new movie called Rhino Season (Fasle Kargadan) by the eminent Iranian film director Bahman Ghobadi. It can also be interpreted as a metaphor for an entire society, haunted by the human rights violations that shattered so many lives, yet unable to move forward because of the Iranian government’s stubborn refusal to accept responsibility for the crimes they perpetrated. Thousands of people were imprisoned, tortured and executed in Iran in the 1980s; there has never been a reckoning, there has been no accountability and it is impossible for any of those scarred by those years to find peace and closure.

Based on the true story of an Iranian Kurdish poet known by the pseudonym Sadegh Kamangar, the film’s main character Sahel was thrown into prison soon after the Iranian Revolution of 1979 solely because of his poetry. He was convicted and sentenced after a travesty of a trial; not only does he endure physical abuse, he has to listen to the screams of other prisoners being tortured nearly around the clock. His beloved wife was also thrown in prison and sentenced to ten years after she refused to sign divorce papers. After she was released with the twins she bore in prison, she was falsely told that he had died and grief stricken, she left Iran.

When Sahel—just a shell of a man after 27 years in an Iranian prison—finally gains his “freedom” he goes to Turkey to look for his wife and her children. Although he locates them, he can only make the most tenuous connection to them; whether they ever learn who he is remains an open question.

The film’s release coincides with a concerted effort being made to both bear witness to the atrocities committed by the Iranian government in the 1980s, and to try to hold those responsible accountable.

In addition to the thousands of people who were sentenced to death and executed in the years immediately after the Islamic Revolution, a series of summary executions of political prisoners called the “prison massacres” took place during a few months in 1988-89 just after the end of the war between Iran and neighboring Iraq. We don’t know how many people were executed during that short span of time, but it could have been 10,000 or even more.

Many of the victims had not even been sentenced to death and had no expectation they were to be killed; in many cases, “trials” were swiftly held in the middle of the night in the prisons, followed immediately by group executions. The victims’ families were not informed that their loved ones would be executed and many were never told the truth about what happened. A large number of the bodies were buried in mass unmarked graves such as at Khavaran Cemetery.

To compound the misery of the grieving families, authorities have violently dispersed commemoration ceremonies held at Khavaran in the years since and have even been bull-dozing and desecrating the grave site, destroying evidence of the crimes. People like Mansoureh Behkish who have tried to bring attention to the lack of accountability for their lost family members executed in the 1980s have themselves been targeted and sentenced to lengthy prison terms.

In June Amnesty International’s UK section hosted the Iran Tribunal Truth Commission on the killings in the 1980s, that resulted in an exhaustive report supported by a number of first-person testimonies. Another session of the Tribunal has been meeting in The Netherlands to continue to collect eye witness accounts and discuss ways of holding Iranian officials accountable. These new projects build on the long-term efforts of committed activists such as those at the Boroumand Foundation who have painstakingly compiled the names and stories of the executed.

The film is also very personal. Sahel is played by Behrouz Vossoughi, a popular actor in  Iran in the 1970s who has been living in exile in the U.S for more than 30 years. The film’s director, Bahman Ghobadi, was forced to leave Iran in 2009 during the upheavals in the wake of Iran’s disputed presidential election. This is his first film produced while living in exile. Both men have been cut off from their former lives in their homeland. Rhino Season is dedicated to the memory of Iranian Kurdish activist and teacher Farzad Kamangar, who was executed in 2010. Kamangar is the “pseudo-namesake” of the poet on whose story the film is based, who also happened to be a family friend of Mr. Ghobadi.

Iran in the 1970s who has been living in exile in the U.S for more than 30 years. The film’s director, Bahman Ghobadi, was forced to leave Iran in 2009 during the upheavals in the wake of Iran’s disputed presidential election. This is his first film produced while living in exile. Both men have been cut off from their former lives in their homeland. Rhino Season is dedicated to the memory of Iranian Kurdish activist and teacher Farzad Kamangar, who was executed in 2010. Kamangar is the “pseudo-namesake” of the poet on whose story the film is based, who also happened to be a family friend of Mr. Ghobadi.

The process of healing from historical traumas such as human rights violations on a massive scale must begin by the acknowledgement of responsibility. Yet to this day, the Iranian authorities steadfastly deny carrying out politically motivated executions. Like Sahel in Rhino Season, who is stymied and trapped by a past and present that bleed into each other, the people of Iran need and deserve a path out of limbo.

I don’t think so it is a justifiable thing to put someone in the prison for just writing a poem. It is totally against the human rights and there is a need of a regulatory authority to make this activities nil in this world.