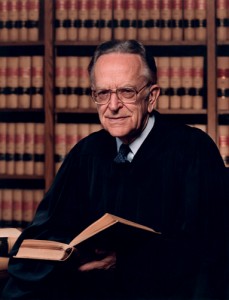

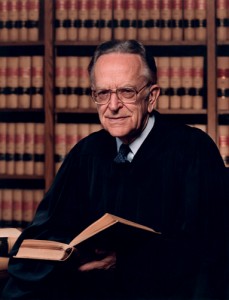

The late Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun regretted the Court's 1976 Gregg vs. Georgia decision allowing executions to resume, saying in his dissent: "The path the Court has chosen lessens us all."

Daniel Cook, abused since infancy and now facing execution on August 8 in Arizona, is just the most current example of someone who endured severe childhood abuse only to later face execution. (Cook has a clemency hearing on Aug. 3; the prosecutor opposes his execution and it can still be stopped.)

There have been plenty of others.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. In its 1976 Gregg v. Georgia decision, the US Supreme Court allowed executions to resume but required that juries be guided to restrict death sentences to the worst crimes committed by the worst offenders (aka “the worst of the worst”). The Court also endorsed laws “permitting the jury to dispense mercy on the basis of factors too intangible to write into a statute.” Defendants with mitigating circumstances (like youth, diminished mental capacity, or a history of childhood abuse) were supposed to receive lesser sentences.

So why do people with severe child abuse in their backgrounds keep ending up on death row? Are they really among the worst? SEE THE REST OF THIS POST