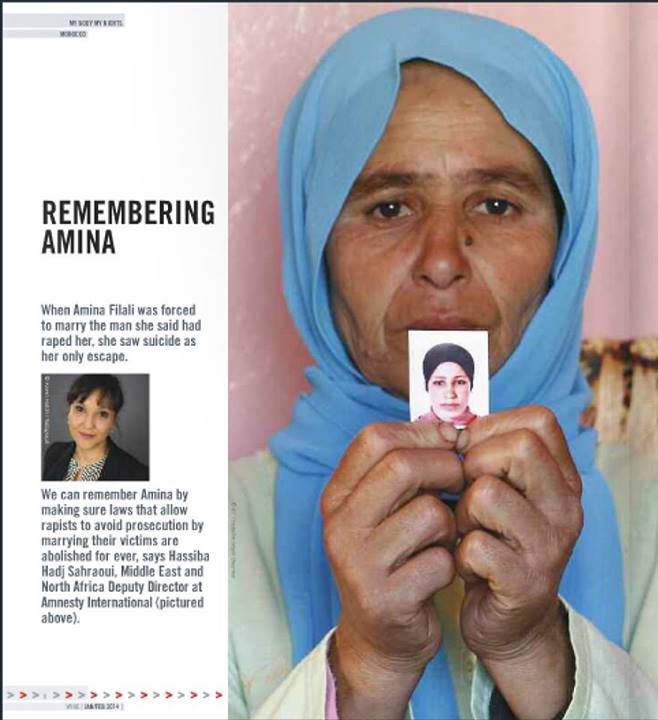

Zohra Filali holds a picture of her daughter, Amina, the week after she committed suicide. Amina took her own life by drinking rat poison in March 2012 after being forced to marry the man who allegedly raped her.

By Hassiba Hadj Sahraoui, Deputy Director of Amnesty International’s Middle East and North Africa Program. This post originally appeared in the International Business Times.

Amina Filali was just 16 years old when, in the depths of despair, she decided to take her own life.

Several months earlier the teenager from Morocco had been forced to marry a man whom she said had raped her.

In March 2012, Amina lost all hope. She swallowed rat poison in her hometown of Larache and died shortly afterwards.

Up until last week, men accused of rape in Morocco were able to escape prosecution by marrying their victim, if the girl was aged under 18.

Nearly two years after Amina’s death, this widely-criticized clause in Morocco’s Penal Code has finally been abolished.

Similar clauses exempting a man accused of rape from punishment if he marries his victim still exist in Tunisia and Algeria.

Sadly, however, for many other women and girls across the Maghreb, such laws continue to pose a major threat.

Similar clauses exempting a man accused of rape from punishment if he marries his victim still exist in Tunisia and Algeria.

Across North Africa, discriminatory legislation continues to fail the survivors of sexual violence.

In Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia rape within marriage is not considered a criminal offence. The definition of what constitutes rape in the eyes of the law also falls far short of international legal standards.

In all three countries, the provisions relating to rape are included within a section of the Penal Code that deals with offences relating to “decency.” This misplaced emphasis views the crime not as an attack on the bodily integrity of the victim but as an attack on “morality.”

It risks women and girls who report sexual violence being subjected to unjustified scrutiny of their actions, and blamed for the violence they suffered.

Further afield in Egypt, sexual assaults and harassment during protests have soared since November 2012, while forced virginity tests were also carried out on female demonstrators in the aftermath of the 2011 uprising.

Throughout the Middle East and North Africa, women continue to be reduced to their virginity or marital status. In Morocco, harsher penalties may be applied depending on whether or not a rape survivor was a virgin.

Too often, a woman or a girl who loses her virginity as a result of rape is shunned by society for having brought the attack on herself. Rape survivors are further stigmatised as their prospects of marriage shrink significantly afterwards.

The shame and feelings of degradation associated with rape in such societies can become a factor in convincing family members to consider forcing a girl to marry the rapist as a viable option.

Instead of being offered support, survivors of sexual violence in the region often find that, like Amina, they have nowhere to turn for help. Changing deep-rooted social attitudes and conceptions will take time. But for this to become a realistic goal, countries in the region must lead the way by taking serious steps to strengthen laws to ensure they protect women and girls from rape and other forms of sexual violence.

Even in Tunisia, a country often hailed within the region for its progressive women’s rights laws, with a newly-approved constitution that enshrines equality between men and women, laws covering sexual violence are still inadequate.

In Tunisia, Morocco and Algeria, comprehensive legal reforms, made in consultation with women’s rights groups, are urgently needed to end discrimination and violence against women and girls. A strong message must be sent to those who commit gender-based violence that they will no longer be able to escape such crimes unpunished.

Laws that criminalize sex outside of marriage – including consensual relations between unmarried adults and consensual, private same sex-sexual activity – also have serious consequences. Such provisions may discourage victims of sexual assault or rape from coming forward to report the crimes to the authorities.

In one case that provoked outrage in Tunisia, Meriem Ben Mohamed (not her real name), a 27-year-old woman, reported that she was raped by two police officers in Tunis in September 2012. When she reported the crime to the authorities, she found herself accused of indecency, instead of seeing her complaint investigated.

Survivors of gender-based violence must have the means to seek justice and reparations for the crimes they have suffered. Police, judges, lawyers and health workers must also be trained to sensitively and effectively deal with women and girls reporting sexual violence.

We cannot let women who find themselves in Amina’s desperate situation feel abandoned any longer. Unless serious efforts are made to cast aside these ignominious laws once and for all and unless the law protects the victim rather than the criminal, many other women are destined meet the same tragic fate.

It is horible to read, that this is still happening in 2014. As a Smnesty International member I really hope this Loophole will be closed fast. Morocco is a nice beautiful country but in this case they still have to do a lot.

I have been involved in community service as a volunteer for about 4 years now here in Fes, Morocco. The place where I go so often to tutor shelters lots of minor girls who have been sexually abused and mistreated, the mojority of them had experiences working as maids. I was so disgusted to learn that in early age they were horrifically sexaully abused by their employees. The saddest thing about their story is that their parents who are supposed in such cases to offer support to their victimized daughters, decide to reject them instead to avoid what they stupidly call "shame". They dont know that the disgrace and the greatest shame is adonding a minor daughter who happened to be in the wrong environment where a woman is treated as a second-class citizen!

Forced marriage is itself a violation of all human rights in this context it also serves as a validation of Rape

it is sad how barbaric is the customs of certain countries that a victim have or chose to marry the person who have committed the rape act against her